Hay bales can cost $10-$25 or $100-$200 depending on size of bale, type of hay, and location. If you have goats, horses, cows, rabbits, or chickens, hay is very important for their food and bedding. It's also a significant ongoing cost. But if you’ve ever tried to compare hay prices, you’ve likely noticed: it’s not simple. Costs vary widely by location, hay type, bale size, quality, and season.

This guide will help you understand:

Hay prices are influenced by a mix of supply, demand, regional climate, and transportation costs. A drought in one place or higher fuel prices can affect how much hay is available and its cost, even in other areas.

💡 Example: In Kentucky, small square grass hay bales average around $7.50. In drought prone areas like Arizona or California, that same bale might cost $12–$18 due to scarcity and trucking fees.

(Source: USDA Market News Reports – Hay)

Prices fluctuate based on proximity to hay-growing regions, fuel costs, and your distance from producers. Here are your best bets for checking prices:

🔍 Search Tip: Try “alfalfa hay square bales near [your town]” or “round bale grass hay delivery [your state]” for local results.

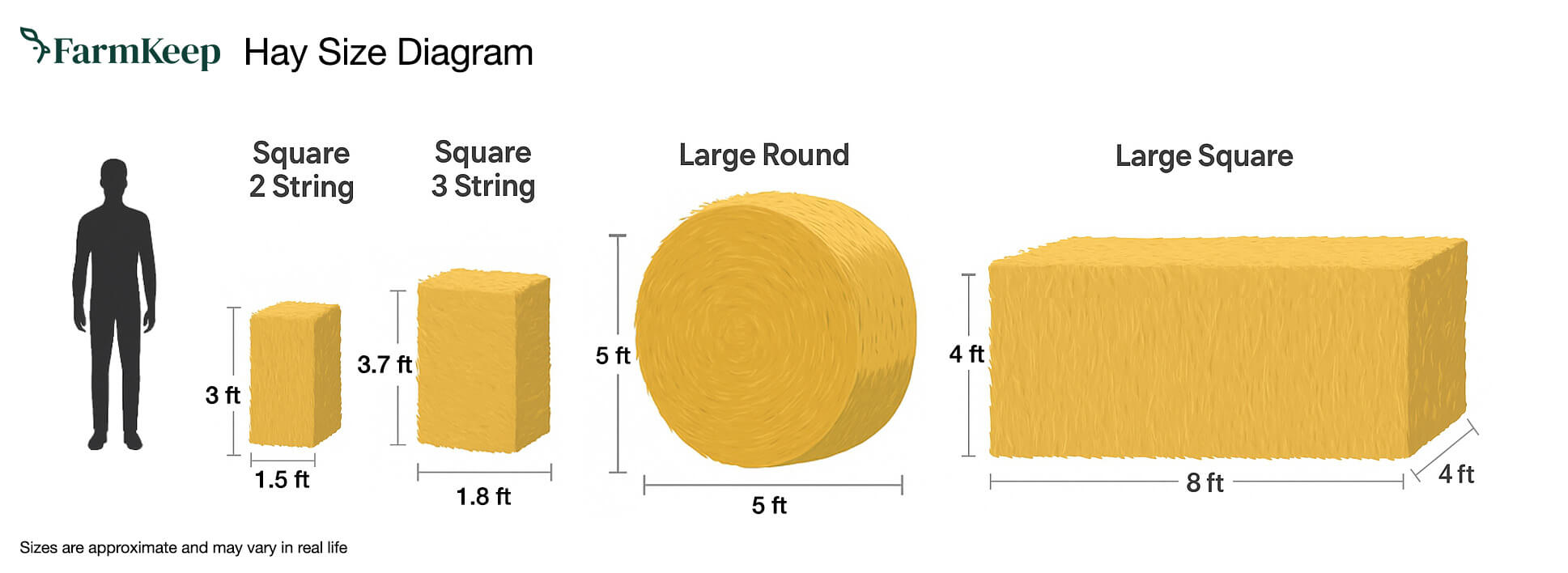

Size affects cost per unit but not always per pound—buying in bulk often lowers your per-pound price. That said, small square bales are easiest to handle without equipment, ideal for small farms or daily feeding routines.

When it comes to feeding livestock, not all hay is created equal. The nutritional needs of your animals will determine whether you choose grass hay, legume hay, or a mix of both. Factors like protein, fiber, and calcium levels can affect animal health. They can influence milk production, weight gain, and digestion safety. This is especially important for sensitive animals like rabbits and horses.

Hay is also classified by its cutting stage (first cut, second cut, or even third cut), which affects both texture and nutritional content. Let’s break it down.

Examples: Timothy, Orchard grass, Bermuda, Fescue, Ryegrass, Oat

Hay for livestock: grass hay is the go-to feed for animals that need high fiber and low protein, making it especially good for:

Grass hay usually has less calcium and protein than legume hay. This makes it better for animals that are at risk for urinary or metabolic problems. It helps maintain healthy digestion thanks to its coarse stems and high fiber content.

Best for: Daily maintenance feeding for most animals, including horses, donkeys, rabbits, alpacas, and pet goats.

Examples: Alfalfa, Clover, Birdsfoot Trefoil

Legume hay is known for its high protein, calcium, and digestible energy, which makes it great for:

However, legume hay is too rich for animals that aren’t actively growing or producing—such as adult wethers, dry does, or easy-keeper horses. Feeding too much alfalfa can lead to issues like urinary stones in male goats or obesity in rabbits.

Best for: High-output animals needing extra calories and calcium. Use in moderation for others.

Examples: Timothy/Alfalfa, Orchardgrass/Clover

Mixed hay combines the protein-rich benefits of legumes with the fiber and digestibility of grasses—making it a great “middle-of-the-road” option.

Look for mixed hay labeled with exact percentages (e.g., “70% timothy / 30% alfalfa”) if you want to fine-tune your herd’s nutrition.

Best for: Multi-species farms or animals in moderate production/growth stages.

The cutting of hay refers to when the grass or legume was harvested during the growing season:

Pro Tip: When choosing hay, ask the seller for the cut and analysis report (many will have basic info on protein %, calcium, and moisture). If you’re feeding pregnant animals or milkers, this info can help you fine-tune their diet.

🐐 Tip: For goats, a mix of grass and alfalfa is ideal. For rabbits and horses, plain grass hay is safest long-term.

(Source: University of Missouri Extension)

🚫 Never feed moldy hay—it can cause respiratory or digestive issues in most animals.

Hay is a crop of grasses or legumes that is cut, dried (cured), baled, and stored for feeding livestock. Unlike straw, which is a byproduct of grain crops, hay is intentionally grown for nutritional value.

Step 1: Planting Hay Fields

The process begins with planting hay crops, typically done in early spring or fall, depending on your region. Farmers pick between different types of grass, like timothy, orchardgrass, or bermudagrass, and legumes like alfalfa or clover. They can also plant a mix of both for better nutrition.

Step 2: Growing to the Right Maturity

For hay to be nutrient-rich, it must be harvested at the optimal growth stage—usually just before blooming. Cutting too early reduces total yield, while cutting too late results in tougher, stemmy hay with less nutritional value.

Monitoring maturity is crucial for producing high-quality hay suitable for horses, rabbits, dairy cows, and other livestock.

Step 3: Cutting the Hay

When conditions are just right—typically warm, dry, and sunny—farmers use a hay mower or swather to cut the crop. The machine lays the hay down in long, even rows called windrows for uniform drying.

Step 4: Drying (Curing) the Hay

Once cut, the hay is left in the field to cure under the sun for anywhere between 2 to 5 days, depending on weather. The goal is to reduce moisture to safe storage levels (under 15%) while preserving nutrient content.

This step is weather-dependent: a surprise rainstorm can lower quality or delay baling.

Step 5: Raking and Baling

After curing, the hay is gathered into windrows using a hay rake. It’s then collected and compressed into bales using a baler—either round or square in shape.

The baler ties each bale with twine, wire, or net wrap to hold the shape and protect from rain and spoilage.

Step 6: Transporting and Selling the Hay

Once baled, hay is either:

Some farmers also sell hay by the ton or bale directly from the field as “first-come, first-served,” saving on storage and labor.

Fun fact: Hay can be made 2–4 times per year depending on the climate and species.

(Source: Penn State Extension)

Avoid retail markups at feed stores. Use Craigslist, Facebook Marketplace, or visit your county ag extension for local producer directories.

Buying by the ton (round or large square bales) brings down price-per-pound—if you can store it properly. Find a friend or another farmer to split the bulk cost with to save money and storage space.

Offer goods or services (manual labor, eggs, firewood) in exchange for hay with neighbors.

If you have land, you can grow and harvest your own grass or legume hay. Tools like a sickle bar mower, rake, and manual baler help small homesteads produce their own feed.

FarmKeep helps small farmers and homesteaders stay organized and save money by tracking:

Download FarmKeep to start tracking your feed inventory and spending now.

The cost of a bale of hay depends on what kind you buy, where you live, and how much you need. But with the right tools, savvy sourcing, and good storage, you can stretch every dollar further. If you have dairy goats, chickens, or cows, knowing about the hay market is important. It helps keep your animals healthy and your farm making money.